Death’s trampoline: a violent inclusion path to the state

By: Ximena Serrano Gil

Photos:

Economics and Politics

By: Ximena Serrano Gil

Photos:

Between the Andes and the Amazon, there is a winding path, penetrating the imposing jungle and contrasting with creepy chasms: It is Death’s Trampoline, something that, in addition to being considered one of the most dangerous roads in the world, tells part of the conflict and construction history of the state in Putumayo.

kilometer, on a 3-meter unpaved single-lane road; there, the dust turns into mud on the unstable ground from continuous rains that accompany the rugged topography of the route, which goes from 600 meters above sea level up to 2,800 meters above sea level. The dense fog and constant landslides only allow one to focus one’s attention and fear on the deep cliffs that have claimed the lives of many persons. This is Death’s Trampoline, which connects San Francisco with Mocoa and connects this border region with the country’s interior.

Understanding how road dynamics reflect the violent ways in which the Amazonia has been included in a discursive and material way in the state is the object of study of Simón Uribe Martínez, who has a Ph.D. in Regional Planning and a Master’s degree in Human Geography, and is a professor and researcher of the Faculty of International, Political, and Urban Studies of Universidad del Rosario. Author of various articles, books, and the award-winning documentary called Suspensión, which refers to the disproportionate construction of a variant in the middle of the jungle that leads nowhere.

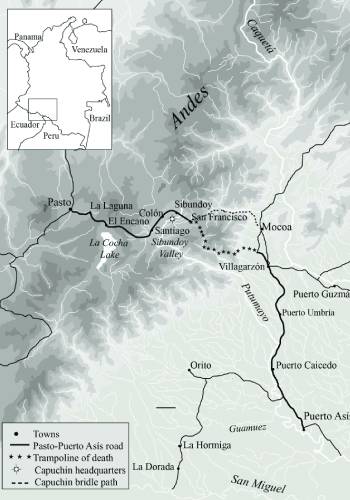

On the heels of his doctoral thesis, Uribe published the book Frontier Road: Power, history, and the everyday state in the Colombian Amazon, in which, through an ethnographic study on the construction of the road that connects Pasto (Nariño) with Puerto Asís (Putumayo), he centers his argument on the role that regions considered borders, peripheries, or margins have had in construction and legitimation of a hegemonic state project.

Workers working in the section San Francisco- Mocoa, c. 1911.

Roads and colonization of the Amazon

The origins of these roads go back to 1909, when the Capuchin missionaries, in their interest to evangelize Amazon indigenous communities, established the Mission’s headquarters in the Sibundoy Valley, between Pasto and Mocoa, and with the government’s support, they began the construction of a bridlepath between Pasto and Puerto Asís, known as the Capuchins path (the predecessor of what would later be the San Francisco- Mocoa Variation, an alternate route to Death’s Trampoline).

Later, according to the investigation made by Uribe Martínez, in the the 1930s, the opening of colonization roads of the Amazon took place. The war with Peru in Putumayo (between 1932 and 1933) forced the government to decree the construction of the Pasto to Mocoa road an emergency measure, given the need to have control over the borders for territorial defense.

In this new project, the engineer in charge, Rafael Agudelo, decided to build an alternative road for the section between San Francisco and Mocoa, which had been built years ago by the Capuchin monks. This is the new layout that has been in operation since 1944, and it is the one known today as Death’s Trampoline.

Because of the high danger that the Trampoline represents, at the beginning of 2000, the government authorized the construction of the San Francisco-Mocoa variant, which follows the same route that the old Capuchin road does; however, and despite being of vital international, national, and regional interest, because it is part of a multimodal corridor that seeks to connect the Atlantic in Brazil to the Pacific in southern Colombia, since December 2016, the work lies suspended because of the lack of economic resources.

But what was the real impact of all this infrastructure? Uribe clarifies that although the government's immediate priority was to facilitate the movement of troops and artillery to establish national sovereignty throughout the region, the importance of these paths has to be located in a larger story of agrarian conflicts and the colonization of the lowlands of Putumayo. “The roads in the Colombian Amazon were, for a long time, the main state policies to colonize the region. This generated many social, territorial, and environmental conflicts that persist to this day,” he emphasizes.

This is how roads are a way of understanding how this region has been colonized and the importance of the roads in the contemporary occupation of the Colombian Amazon.

Infrastructure violent dynamics.

hese roads are so precarious that for the region’s inhabitants, it became part of the landscape and synonymous with abandonment or state absence. However, as the expert says in the conclusions: “The problem is not state exclusion but the way in which these regions have been violently included into a dominant political and social order of the state. It is not the absence of the state, but the way in which they have been incorporated,” argues Uribe, who challenges the concept of “absence of state,” because he assures that it has to do with the way in which the state has been traditionally conceived.

In accordance with the general approaches of the investigation, under the concept of infrastructural violence, the different forms of integration and inclusion that are produced or maintained through built environments are critically analyzed.

Vía Pasto–Puerto Asís. Section of Death’s Trampoline and the Capuchin road.

According to the researcher, in infrastructures such as Death’s Trampoline, that form of violent inclusion is expressed not only in the physical space of the road but also in the way in which the existence of this space is assumed as “normal.” On the other hand, it is a form of violence expressed in many aspects of daily life in the region, and from a long-term perspective, it has been instrumental in its assimilation of the state’s

political order.

Therefore, Uribe concludes: “Borders have played a discursive role in the construction of a hegemonic project of Nation-State in Colombia, specifically in their representation as spaces whose integration into the state requires its pacification or civilization. One of the objectives of the investigation is to understand how this discursive construction materializes through roads or in broader terms to analyze the relationship between discourses and material practices of the state in the configuration of spaces that are considered border or marginal.”

The documentary as a knowledge tool

One of the challenges of this cinematographic bet for Simón Uribe was adapting scientific language to audiovisual: “I wanted to tell that story through a different medium, such as the audiovisual, not to make it a version of the book, but to approach some aspects of story from the audiovisual point of view. This has to do with the interest of transmitting knowledge differently, and the documentary allows, through simpler language, to interact with audiences that are not exclusively academic.”

This production was selected in the category best first film in Idfa (Amsterdam), one of the most prestigious documentary film festivals worldwide. After Idfa, where Suspensión had its world premiere, the documentary has been selected in numerous festivals, such as the Cartagena International Film Festival, Docs Barcelona, Trento’s Film Festival, and DokMunich, among others.

knowledge generated from the academy to other spaces where usually researchers cannot reach. The

documentary allowed me, through the images and voices that intervene in it, to make an ethnographic discourse analysis by telling a story and getting the message across.”

Simón Uribe Martínez, researcher of Faculty of International, Political, and Urban Studies of Universidad del Rosario, explains that his object of study is to understand how road dynamics reflect the violent ways in which the Amazonia has been included in a discursive and material way in the state.