Lessons from natural disasters and pandemics can help us cope with the new reality

By: Marisol Ortega Guerrero

Photos:

Environment

By: Marisol Ortega Guerrero

Photos:

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which appeared in China in 2003 and rapidly spread to America, Europe, and Asia; Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which hit the southeastern United States and resulted in the largest death toll and economic damage in U.S. history; and the 2017 earthquake in Puebla, Mexico, which killed 350 people and caused extensive property damage. These are some events that have provided a reference to scientists on managing the physical and emotional health consequences in catastrophic situations. Their interest is to contribute to science and, from another perspective, to deal with the greatest health emergency of the last hundred years: the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers from Colombia, Chile, and Spain are in charge of this important mission. For months they have immersed themselves in the existing literature on the crises that have occurred in the world; in addition, they have analyzed the results of an inquiry they conducted in June 2020 among undergradu - ate and graduate students to determine how the students felt, how they dealt with the situation characterized by confinement, and whether or not they were anxious.

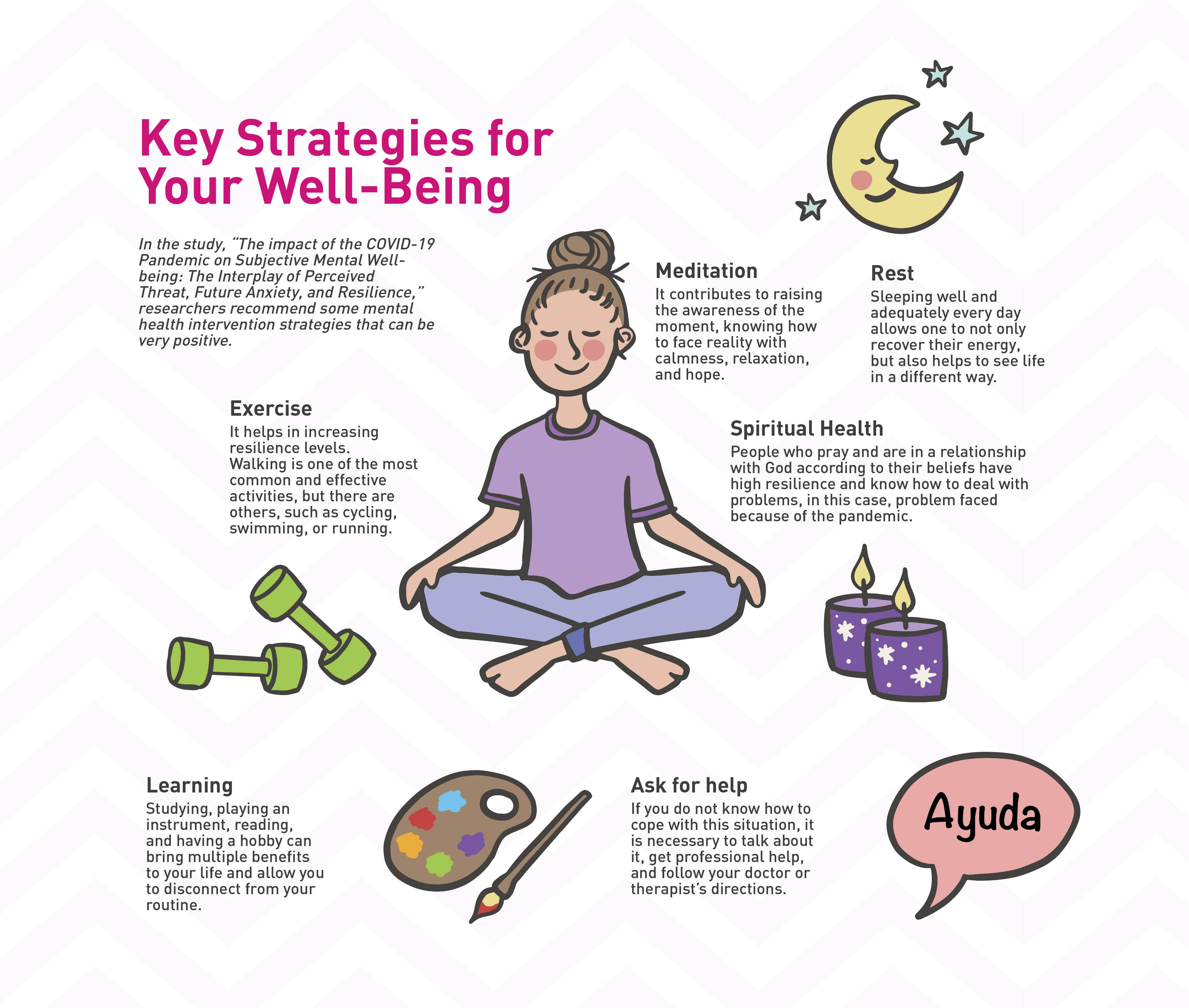

Based on the findings of that inquiry, practices such as teaching individuals about healthy lifestyle practices, encouraging a culture of self-care, and providing knowledge on emotion regulation could help mitigate the pandemic’s harmful psychological effects.

“In the face of a threat that causes great concern, fear, and dread, increases anxiety levels, affects the well-being of people, and makes them feel vulnerable, stressed, fragile, and sad, as documented in studies conducted by the University of Southern Mississippi on Hurricane Katrina or by the University of Hong Kong on the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong research investigations such as those stated above have examined psychological resilience, despair, and dysfunction among survivors,” states Professor Mario R. Paredes, of the School of Business Administration at Universidad del Rosario, Colombia’s participating institution.

He, in cooperation with Vanessa Apaolaza and Patrick Hartmann, , professors at Universidad Del País Vasco (UPV) in Bilbao (Spain), and Cristóbal Fernández Robin and Diego Yáñez Martínez, from the Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María in Valparaíso (Chile), published a study called “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subjective mental well-being: The interaction of perceived threat, future anxiety, and resilience.”

The researchers administered 711 valid ques - tionnaires to men and women between 18 and 49 years of age. Approximately 72% were undergraduate students, and 28% were grad - uate students. Using the obtained results, they contrasted the proposed hypothetical relationships using measurement scales pre - viously developed in the literature. For exam - ple, Zaleski’s (1996) scale for measuring future anxiety is understood as a set of behaviors in which the fear of future events predominates.

Although there was a low response rate (4%), which is explained by the fact that this was a voluntary, non-incentive survey, solic - ited at a time when a high volume of information n related to the new coronavirus was being received, the results allowed them to confirm the conclusions drawn from past research. For example, a pandemic is one of those significant events that are out of the ordinary, similar to large-scale natural disasters (e.g., tsunamis, tidal waves, and earthquakes) or wars, and affect the mental health of people across short, medium, as well as long terms.

The dimensions of these effects and an individual’s response to them are determined by resilience, which is considered a personality trait that allows effective coping with stressful or traumatic events and even with life itself. A characteristic found in every person. In athletes, it is an obvious trait because their degree of resilience is what allows them to face adversities, overcome failures, recover from a serious injury, and resume their activity.

“We measured it as a personality trait,” explains Paredes. “We are all endowed with different levels of resilience and, in the case of the pandemic, it is a reality that people who have a higher degree of resilience feel a lower threat ratio in the face of this new reality. Thus, they minimize the negative impact of anxiety on the subjective well-being.” Mindfulness is another topic that has been found to be positively related to resilience levels. Researchers define it as living in the present without judgment, focusing our attention on it, and increasing self-awareness, which can be achieved through meditation techniques.

Mario R. Paredes, a professor at the School of Business Administration at Universidad del Rosario, claims: “We are all endowed with different levels of resilience and, in the case of the pandemic, it is a reality that people who have a higher degree of resilience feel a lower threat ratio in the face of this new reality. Thus, resilience minimizes the negative impact of anxiety on an individual’s subjective wellbeing.”

According to Professor Paredes, “Mindfulness can also be understood and studied as a personality trait. Those who come equipped with this trait strongly achieve a deep state of awareness of what they are experiencing, their feelings, and thoughts, and this in turn influences their perception of well-being and future anxiety. Consequently, it allows them to live better and be less susceptible to the harmful effects of perceived threats, in this case, by COVID-19.” This implies that “individuals with higher resilience are less susceptible to the pandemic’s negative psychological consequences because they experience a lower increase in anxiety about the future, compared to individuals with lower levels of resilience,” explained the authors in the article published in February 2021 in the journal Personality and Individual Differences.

However, researchers highlight the major risk accompanying the pandemic, which has not only caused mental problems but has changed, to an unprecedented magnitude, the way we relate and live together.

“We have to be clear that we need welfare to function as a society. We all have coping mechanisms that help us deal with the stresses of everyday life; some have more than others. However, when there is an imbalance, and as an individual, I cannot cope with the challenges presented to me on a daily basis, I cannot develop myself in a way in which I can contribute to the community,” concludes Professor Paredes.

The authors of this study emphasize that subjective mental well-being is related to the emotional state of the individual, based on his or her own background and on the biological, cultural, psychological, and social factors that converge, as well as on what the person perceives about the environment. The media, for example, plays a significant part in this because it can both inform and provoke anxiety levels.

They argue that anxiety about the future is a dimension of time that comprises negative cognitive and emotional behaviors and processes that are dominated by the fear of future events. There is an unjustified anticipation of changes perceived as supposedly dangerous or adverse.

Finally, resilience is seen today as a personality trait that imparts the ability to positively adapt to adverse situations. This characteristic positively moderates the relationship between a perceived threat and anxiety about the future, with an impact on subjective well-being.

For this reason, researchers advise working to strengthen resilience. Among other activities, this involves a healthy lifestyle that includes exercise, rest, and recreation.