The right to memory

By: Magda Páez Torres

Photos: Alberto Sierra, Milagro Castro, Juan Ramírez - https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.36801_num6

Society and Culture

By: Magda Páez Torres

Photos: Alberto Sierra, Milagro Castro, Juan Ramírez - https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.36801_num6

Gladys Durán lost her brother and her nephew, on a day in January, 22 years ago, while they were making a living by carrying groceries to Bosconia (Cesar). Since then, she and her family face a never-ending calvary, crammed with questions that, up to now, have not been answered. “Because of the need for getting crumbs of money, they left and lost their lives. We want to know what happened to them, so we can, at least, recover their bodies. For the time being, there is no information, they have been swallowed by the earth,” she states in a begging tone..

Just as she does, thousands of families in the country live in incomplete grief; they eagerly look for answers about the destiny of their beloved ones, who, rather than by the earth, were swallowed by violence. According to the final report by the Truth Commission, presented on June 28, over 400,000 people were fatal victims of the armed conflict in Colombia between 1986 and 2016, without taking into account kidnappings and forced disappearances.

Priest Francisco de Roux, president of that body, puts it in other words: “It would take us 17 years to offer a minute’s silence to each victim.” Today, as the Peace Agreement with the FARC is under implementation, the truth seems to be a balm for the poorly cured pain of so many Colombians who expect to give peace to their hearts by retrieving the bodies of their beloved ones, tracking their last movements, and leaving flowers at any vacant lot where they have exhaled their last breath.

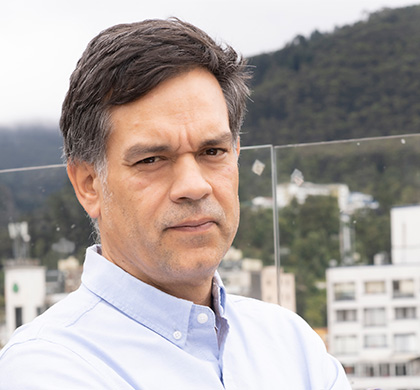

Precisely, to go deeper into that structure implied in the right to memory and truth, professors Ana Guglielmucci and Esteban Rozo, from the Group of Studies on Identity and the School of Human Sciences, Universidad del Rosario (URosario), analyzed the advances and obstacles that came along for the creation of the Museum of Memory in Colombia, a place that will recount the events of the armed conflict, with a view to symbolically remedying both the victims and the Colombian society.

“We decided to observe how this future museum was getting in motion and the transformations it had gone through because of the changes the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, CNMH (National Center for Historical Memory) was undergoing, what situations were happening in that institution, that was going to take into their hands what has been constituted as a national memory of the armed conflict,” Professor Ana Guglielmucci ascertains.

“The museum is in charge of broadcasting, among other issues, the findings of the Truth Commission of spreading a narrative of the armed conflict that may do justice to the claims of the victims”— Esteban Rozo, professor at the School of Human Sciences, of Universidad del Rosario.

Today, Colombia has a Comprehensive System for the Truth, Justice, Compensation and No Repetition, created by provision 5 of the Peace Agreement. This structure is made of the Truth Commission, CEV; Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, JEP (Special Jurisdiction for the Peace); and Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas Desaparecidas, UBPD, (Unit for the Search of the Disappeared). All of this add up to the work of the National Center for Historical Memory, CNMH, whose accumulated results should be handed to the Museum of Memory. However, as the investigative work done by the scholars of URosario summarizes, the creation of this Museum, which was announced on April 9th, 2015 by President Juan Manuel Santos and the then director of the CNMH, Gonzalo Sánchez, it has been a road laden with difficulties, so the process has been stalled.

The greatest controversy broke out with the government change in 2018, during the four-year administration of president Iván Duque, with the appointment of Rubén Darío Acevedo as director of the CNMH, who has been strongly questioned because he would not recognize the existence of an armed conflict in the country.

“Denying the very existence of an armed conflict is problematic. That implies an act of epistemic violence, that is to say, it is assumed that everything was a conspiracy by the guerrillas or the terrorists that intended to put down the order, the State and so on; they are denying, for example, the victims of State crimes, of the armed forces, and a number of consequences come along after those acts,” Professor Esteban Rozo argues.

That was just the triggering event of countless differences that would later get unleashed. A series of changes were made to the script that had been designed by the previous administration, which had been agreed upon with the victims.

“We did some research work in the archives and found that the military, other social and intellectual sectors which are sympathetic to the project of the Central Democratic party, among them former director Acevedo, were implementing an agenda in the CNMH and putting their own policies of memory into practice,” the researcher points out.

“They started to roll like a loose gear, to compose a script with a narrative that is contrary to what had been stated and agreed upon; they exploit that basic consensus from the inside, without sharing it with the JEP or with the Truth Commission, because, at the end of the day, they do not believe in what they are doing,” he adds.

It is worth highlighting that, in 2013, the publication of the report: “Stop it: Colombia, memories of war and dignity” by the CNMH had already shown that controversy, since it exposed the Military Forces as responsible for selective murders, extrajudicial killings, massacres, disappearances, and forced displacements. Organizations such as the Asociación Colombiana de Oficiales en Retiro (Colombian Association of Retired Officers, ACORE) manifested their rejection as they deemed the report was an insult. And even many sectors requested the National Government to withdraw it, but the claim was disregarded by the CNMH.

Professor Guglielmucci considers this type of disputes damage the truth. “What we are seeing here are government policies, not State policies, as a memory policy is supposed to be grounded in the remedy for the victims, due to all the violations to human rights. In general, this sort of museums seeks to achieve some learning from these experiences, instead of standing exclusively from the perspective of one of the actors. This is about elaborating narratives of the truth, but above all, boosting the recognition of the damages caused to them, and thinking about the role of everyone in the conflict, as part of a society and of the State, which should guarantee the rights,” she emphasized.

Another turning point towards the creation of the Colombian Memory Museum was the organization, carried out by the CNMH, of the exhibition Voices to transform Colombia, a traveling fair about the armed conflict, conceived with the participation of different groups of victims. The idea of a “living museum,” led by curator Cristina Lleras, started facing problems in 2017 due to the measures implemented at the end of Juan Manuel Santos’ government and were increased with the change in the direction of the CNMH by the end of 2018.

The study explains, quoting the then rector (President) of the Museum of Memory, Rafael Tamayo, that “Acevedo erased the introductory texts of the exhibition, he changed the contents of the printed flyer and eliminated words like “war,” “spoils,” “resistance” and “resilience” and that, additionally, “in Cali, he intended to erase the whole chapter on the Patriotic Union,” which finally did not happen, seemingly because the team opposed to that. Nevertheless, the research by Universidad del Rosario reveals that they erased the image of Pedro Antonio Marín, nicknamed Tirofijo, from one of the posters as they judged it as “proselytizing and pamphleteering.”

Due to incidents like those, groups of victims like Asociación Minga and Madres de Falsos Positivos de Soacha y Bogotá (Mothers of False Positives from Soacha and Bogotá, Mafapo) withdrew the documents and objects they had contributed to the CNMH, as recorded by the investigation.

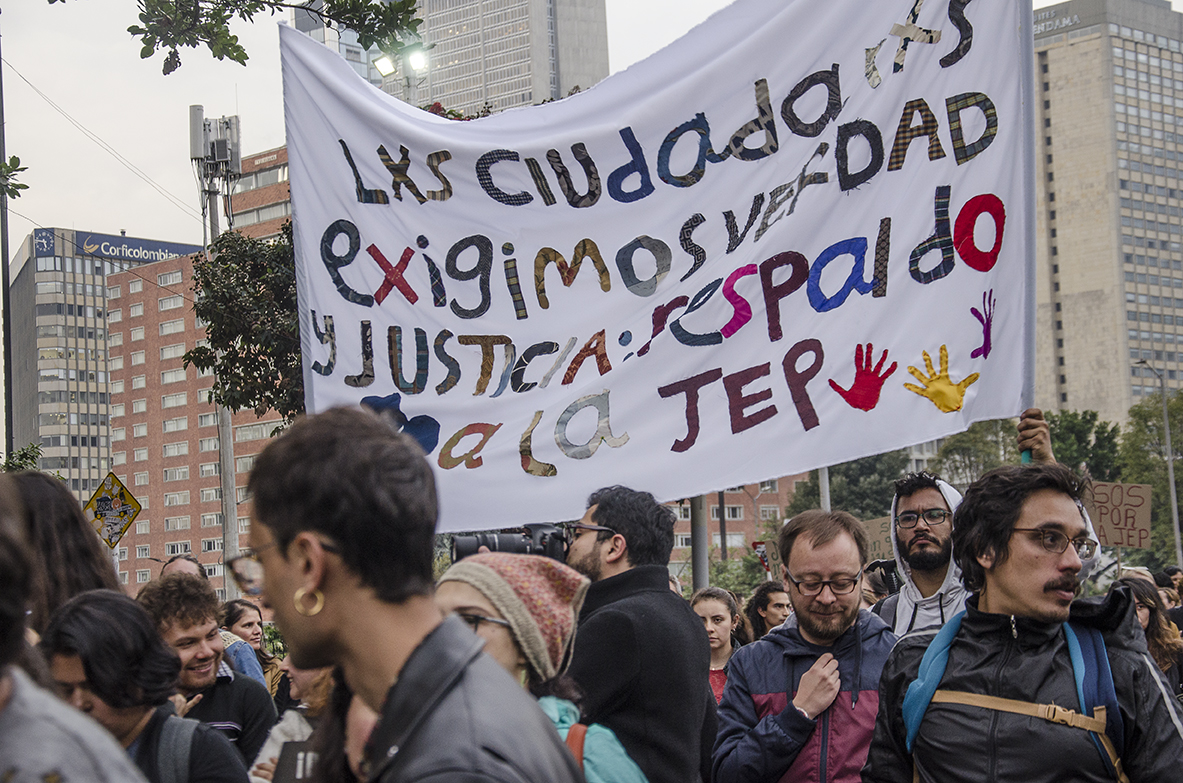

The disagreements were so many that the JEP enforced temporary preliminary measures on the exhibition (File 058 on May 5th, 2020) to preserve it. Although the CNMH submitted an interlocutory appeal, it was rejected.

“I think the JEP intervenes precisely because it is a way of saying that there are Colombian State guidelines that must be followed, and that the agreements made with society cannot be bypassed, counting on the international cooperation which has invested a lot of money to these kinds of policies and to compensate the victims of the conflict. Breaking constantly the accords –the collective work– causes damage, because the trust in this institution gets breached,” as specified by researcher Guglielmucci.

“We are seeing government policies, not State policies, whereas a policy of memory must be grounded on remedying the victims for all the violations to their human rights” — Ana Guglielmucci, professor at the School of Human Sciences of Universidad del Rosario.

Today, as the country managed to reincorporate a good number of the oldest guerrilla in the continent and sought to heal the wounds, on the way to a post-conflict scenario, Universidad del Rosario’s researchers agree on the need to recognize responsibilities to get to stop the spiral of violence.

“These hegemonic narratives recounting the past are connected with the present, with the capacity to build our lives in the future, and that is why they are important. For that reason, we want to show the relevance of the public policies regarding memory and these museums, of setting some narratives that are not just discourses, or statements without any kind of power, but as tools to legitimize other policies, like land restitution,” Guglielmucci comments.

This thesis is complemented by professor Rozo, who claims that “depending on how these narratives on the past are told, the positions are taken, the very contents and all the topics related with the truths about the armed conflict in Colombia, we will stand some chances, or not, of building a different future.”

Although a lot is said about reconciliation amidst the effort for peace, Guglielmucci underlines that it is a progressive process and that the first step for the victims is to find answers.

“Unlike the way these processes were elaborated in other places, like Argentina and Chile, where the victims’ organizations have given more importance to the truth than forgiveness or reconciliation, I think the report by the Truth Commission and the hearings conducted by the JEP are going to enable, precisely, the achievement of this alleged reconciliation process in a much more realistic way.

Therefore, the museum is in charge of broadcasting, among other issues, the findings of the Truth Commission, of spreading a narrative of the armed conflict that may do justice to the claims of the victims and does not focus so much on the topic of reconciliation as a moral duty.”

As Gladys Durán points out, the only redemption for the grief of loss is, eventually, the truth, although –regrettably– for the mothers of her brother and her nephew, the answers are late; they departed to their graves without comfort to their grief. “They left with that suffering, with the affliction of not knowing about their sons. That’s very hard, I hope one day we get answers, and get to understand what happened to them. Our Holy God knows what a burden that would take off our shoulders; I’m very old, but I would go wherever it takes to pick up the remains of my dear brother,” she confesses.

In the middle of this process that seeks the truth, academia plays a key role in delving into the diverse phenomena, analyzing the circumstantial realities and offering ways that may strengthen the construction of peace.

“Academia plays an important role, the whole educational issue of teaching the young, involving the students and motivating them to conduct their own investigations,” Guglielmucci adds. “It is necessary to keep an eye on how academia goes out on the streets, gets to other countries, to other audiences. Above all, contrasting information, checking up, validating in some way the report on the truth.”

Specifically, to contribute actively in this circumstance that Colombia is living, Universidad del Rosario has opened the Master’s degree in Conflict, Memory and Peace as well as the Post-graduate degree in Education for Peace and Citizenship Competencies. The objective is that the young have a leading role in this matter.

The country is undergoing a process of social learning, which involves all actors. It was more than half a century of incubating violence, hatred, pain, and division.

The country is undoubtedly undergoing a process of social learning that involves all actors. It’s been more than half a century incubating violence, hatred, pain, and division. Time and contributions from different sectors are required for the whole de-escalation of the conflict and the construction of stable peace, as the researchers remark. On this path, the Museum of Memory in Colombia, beyond its symbolic nature, takes on the dimension of a right and a space for construction and transmission for those who eagerly seek for the comprehension and recognition of the damages, suffering, and resistance, facing violent situations in the context of the armed conflict. As Father Roux has appropriately put it, “if there is future, it is because there is truth.”